Krzysztof Wodiczko, City Hall Tower, Kraków, 1996

In the Kraków projection the artist for the fi rst time used moving image and sound, using video projectors and

speakers instead of slides and slide projectors. He combined here the experience of his previous monumental

public projections with the social action of his communication-serving Instruments. The use of new technologies

made it possible to give a voice to those marginalized in public life. The projection’s protagonists were victims

of family violence, disabled people, homeless people, drug addicts, homosexuals, HIV carriers. The images of

their hands — gesticulating, peeling potatoes, holding a cigarette or a candle — were projected on the 14thcentury

City Hall Tower standing in the Market Square. Over the course of three nights, October 2–4, the tower,

identifi ed with the speaking persons, “spoke” with their voices and gestures to the crowd below. The half-hour

projection, looped into a two-hour recording of highly intimate confessions, broke the public silence about

issues such as social exclusion, violence, crime, alcohol or drug abuse.

Organized by Bunkier Sztuki Contemporary Art Gallery, the Andrzej Wajda Festival, and the City

of Kraków as part of the Kraków 2000 celebration, with the co-operation of Women’s Centre

coordinator: Beata Nowacka-Kardzis

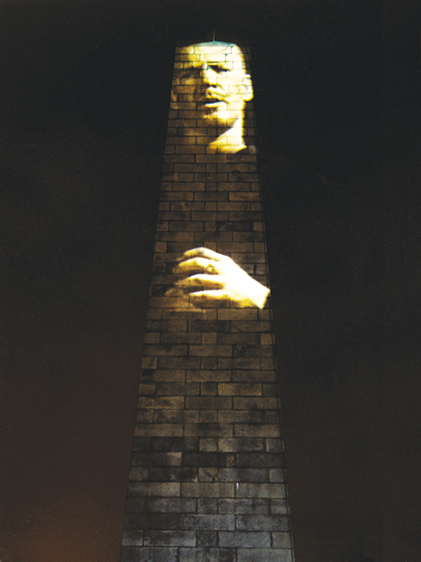

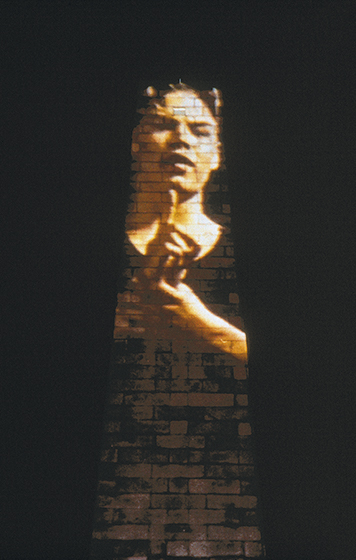

The projection took place on three consecutive nights, September 24–26, 1998. The Bunker Hill Monument

is Boston’s most famous public monument, commemorating the fi ght for freedom during the American

revolution. The construction of the granite obelisk in Egyptian style started on the 50th anniversary of the Battle

of Bunker Hill, fought between American colonists and British troops in 1775. Completed after seventeen years,

the 221-foot structure stands on Breed’s Hill, the highest hill of Charlestown, Boston’s working-class district

that has a particularly high murder and violence ratio, especially among young people. The artist transformed

an historical monument devoted to freedom fi ghters into a monument of contemporary heroes trying to fi ght

violence. On top of the huge obelisk were projected images of the faces of people recounting their experiences,

mothers of murdered children or young people who had lost their brothers or sisters. Shown from the waist up,

they held candles or portraits of their dead loved ones, the huge images of their faces enlivening the monument

and their painful confessions and testimonies breaking the borough’s conspiracy of silence. Aimed at giving

a voice to the aggrieved, the projection was co-organized by the Charlestown After Murder Program, a support

group for victims of violence founded by local mothers who had lost their children to violence. The 19-minute

looped projection featured the testimonies of three mothers and two brothers of murdered persons.

Organized as part of project Let Freedom Ring by the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA/Vita

Brevis) in Boston

curator: Carole Anne Meehan

The projection was carried out on February 23–24 in Tijuana, a city located right by the Mexican-US border and

in the middle of the maquiladora belt, a border-adjacent concentration of manufacturing and assembly plants

run by international corporations using low-cost Mexican labor. The site of the projection was one of the city’s

symbols, a cultural center comprising theaters, museums, galleries, restaurants and so on. Images of the faces

of the projection’s protagonists were projected on the huge spherical shape of the Omnimax movie theater. The

artist had worked with a group of Mexican women who now spoke about their often traumatic experiences,

sexual harassment at the workplace, domestic violence, family disintegration, police brutality. The pre-recorded

statements were interrupted and rounded out live in response to viewer reactions. In Tijuana the participants

took part in the projection live for the fi rst time, thanks to a special head-mounted device comprising a camera,

a microphone and a portable transmitter. Blown-up to huge dimensions, the “live” faces of six women and their

amplifi ed voices, speaking of issues that had until now been mostly taboo, meant the projection spectacularly

claimed the city’s public space. During his year-long preparations for the project, the artist worked with local

women-supporting organizations, Factor X and Yeuani.

Organized as the final event of InSite 2000, the Border Art Festival of San Diego and Tijuana

curators: Michael Krichman and Carmen Cuenca

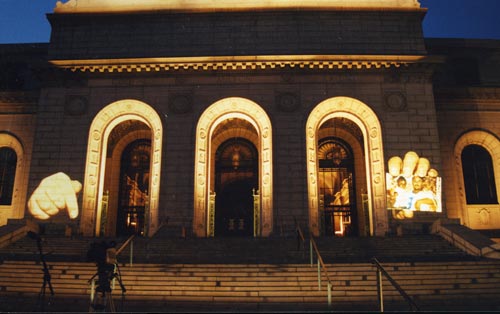

Krzysztof Wodiczko, The Central Library, St. Louise, 2004

The projection on the building of St. Louis’s main public library dealt with the consequences of violence

and the therapeutic potential of public discourse. Participants included both the victims of violence and the

perpetrators. Over the course of three nights, April 16–18, confessions were played back over loudspeakers of

six St. Louis residents who had lost their loved ones to violence and of inmates serving sentences at the Potosi

Correctional Center prison. Their highly moving testimonies were accompanied by images, projected on the

library building’s neo-renaissance façade, of gesticulating hands, seemingly emerging from inside the building,

which was enlivened by the gestures and voices of people speaking publicly about their traumatic experiences.

During the projection, pre-recorded testimonies were mixed with live comments. Some of the participants spoke

from a studio inside the library and members of the audience were able to use a microphone installed outside.

According to the original concept, the projection was to take place on the façade of the historical St. Louis court

building, but a week before the planned date the federal administration withdrew its permission.

projection accompanying the international symposium Critical Praxis for the Emerging Culture:

A Collaborative Investigation into the Nature of Cultural Transformation Brought about New

Media, organized by the Washington University School of Architecture and the School of Art

at the Washington State University, St. Louis

Coordinator: Bob Hansman

The projection took place on 14 November 2005 on the façade of the Zachęta National Gallery of Art building

in Warsaw. The distinguished building in Warsaw’s historical downtown resounded with the voices of women

whose images the artist projected on the two pilasters supporting the neo-baroque building’s tympanum.

The projection dealt with the unequal status of women, their problems, traumas, psychological and physical

domestic violence, alcohol abuse. The images of women supporting above their heads the portico’s entablature

with the inscription “Artibus” [To the arts] were represented in the role of caryatids, an ancient Greek term that

originally meant women sold into slavery. The mute caryatids in the twenty-minute looped projection spoke

with the voices of women carrying the burden of various traumatic experiences. Hailing from the city or the

country, they spoke of enslavement and humiliation, talking to each other or directly to the audience.

Projection organized in conjunction with Monument Therapy, the artist’s solo exhibition at the Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw

curator: Hanna Wróblewska

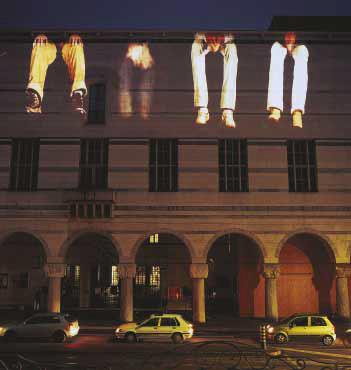

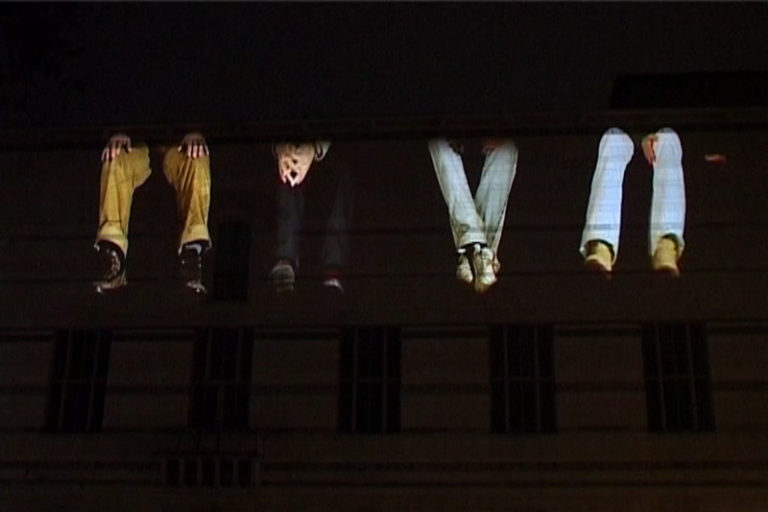

In the projection, carried out on 23 February 2006 on the building of Basel’s prestigious Kunstmuseum, the

artist gave a voice to Switzerland’s illegal immigrants, commonly known in French as the sans-papiers [people

without papers]. Living in the gray zone and usually invisible, they were now made visible in the very heart

of the city’s public space. The moving image projected on the upper part of the building’s façade made the

impression as if four immigrants were sitting on the roof, talking to each other and sometimes doing a little bit

of singing in their native tongues. The viewer could see only their legs dangling from the roof of the museum

and gesticulating hands, while the faces and fi gures remained invisible. In a casual conversation, two men and

two women talked about their lives and their experiences as illegal immigrants. Out of a total of six hours of

footage, the artist selected a seven-minute recording that was presented as a loop.

Projection organized in conjunction with the exhibition Flashback. Revisiting the Art of the

1980s in Kunstmuseum Basel, and with the assistance of Sans-Papiers, an organization working

with illegal immigrants

curator: Philipp Kaiser

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Adam Mickiewicz Monument, Warszawa, 2008

The projection took place on 30 January 2008, the 40th anniversary of the banning of National Theatre’s

fi nal performance of Adam Mickiewicz’s Dziady, taken off the bill on the orders of the then state and Party

leader, Władysław Gomułka. Student demonstrations protesting the show’s banning started a major political

breakthrough known as March 1968. On the monument of the author of Dziady, Poland’s national poet, the

artist projected the images of the faces of actors reciting his poems, their voices alternated with fragments of

Gomułka’s speech, his face projected on the clouds of artifi cial smoke fl oating on both sides of the monument.

Projection organized by the National Theatre, Warsaw

Krzysztof Wodiczko, The Veteran’s Flame, Wzgórze Partyzantów [Partisans Hill], Wrocław, 2010

The projection took place against the background of a 19th-century colonnade symmetrically surrounding a square that became filled with war veterans’ voices. On the colonnade’s middle arcade was projected the filmed image of a candle lame moved by the speakers’ breath. A similar synchronization of image and sound had been used by the artist in The Veterans’ Flame presented a year earlier in Fort Jay on New York’s Governors Island. In Wrocław, he chose the site of Partisans Hill, a place centrally located in the city but seldom visited by its inhabitants, and one marked by history: the remnants of a former bastion in the city’s fortification system, turned in the 19th century into a leisure ground, with elegant buildings and a viewing tower. In 1932, a monument to German soldiers who had lost their lives in the colonies was erected in this then-German city, and towards the end of World War II the city’s central military command headquarters was located in tunnels under the hill. Run-down after the war, then revitalized, and recently run-down again, the place became the scenery in which Polish war veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan spoke for three days about their experiences and traumas and the impact of those on their daily lives.

Organized for the 10th International Film Festival New Horizons.

Curator: Beata Nowacka-Kardzis.

In the projection, carried out on November 9–10, 2010, the artist worked with Polish veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan using a decommissioned Honker Skorpion 3 military vehicle of the type used by Polish troops in Iraq. The weapons platform at the back of the vehicle was replaced with a “projection platform” with audiovisual equipment through which sounds and images were “fired.” Projected on the front walls of Warsaw’s buildings, the texts spoke of issues faced by Polish war veterans and their families, their traumatic war experiences and difficulties in adapting back to civilian life. The projection had been preceded by a workshop with the veterans and their family members, during which sound

recordings were made. Selected material endorsed by the participants was then turned into an audiovisual projection using special computer software. The veterans participated in the “shelling” of the city with their testimonies in several places in Warsaw: on the first day, on the side wall of a building very close to the elegant Krakowskie Przedmieście high street and the façade of the Grand Theater – Polish National Opera, and on the second day, on the façade of the Warsaw University of Technology building and the tympanum of the baroque Krasiński Palace.

Organized by Profile Foundation, Warsaw, with the support of the City of Warsaw and the United States Embassy in Warsaw, and in collaboration with the Association of Poles Wounded or Harmed on Foreign Missions.

Curator: Bożena Czubak.

Software designer: Robert Ochshorn.

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Abraham Lincoln: War Veteran Projection, New York, 2012

In Abraham Lincoln: War Veteran Projection, carried out in November 2012 at New York’s Union Square, the voices and images of Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan veterans were projected on the 143-year-old statue of the US president and veteran of the worst war in US history, Abraham Lincoln. The images of contemporary veterans were projected on a monument of a historical figure, inscribing themselves in its symbolic status, while the statue lent them its moral authority. The monument became a medium through which the veterans shared their experiences in public space. For a month the immobile statue was animated with gestures and voices that made it part of the public debate on war and the fate of veterans. Updated in its symbolism, the Lincoln statue had earlier been a silent witness of numerous protests against the Iraq war staged in Union Square.

The façade of the Mechelen city hall was transformed into an audiovisual communication medium for immigrants. Special software made it possible to record the eyes of the persons who gave their testimonies for the project. Magnified images of eyes looking at the city from the façade of the 13th-century building were accompanied by sound: the voices of immigrants speaking about their traumatic experiences, resounding from a building of symbolic significance and usually inaccessible for them. The artist conducted a series of interviews and recording sessions with immigrants thanks to the support of the local organization Werkgroep Integratie Vluchtelingen.

The projection was part of the exhibition Newtopia: The State of Human Rights.

Curator: Katerina Gregos.

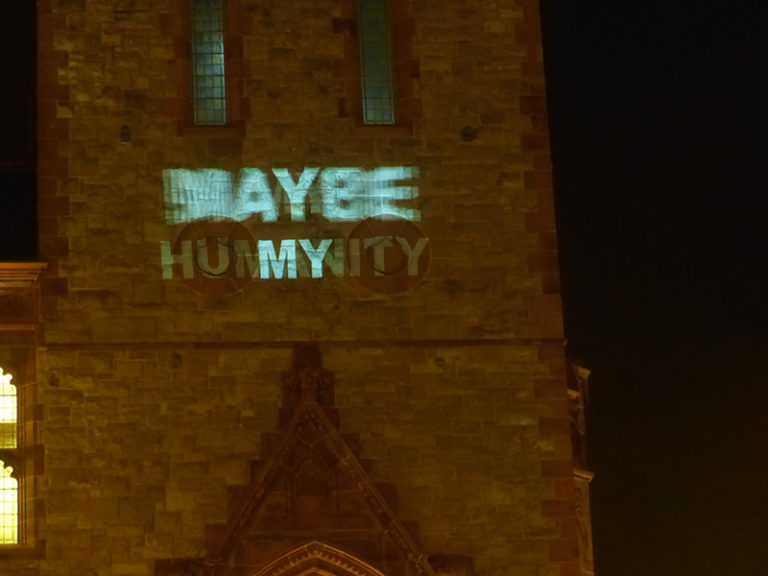

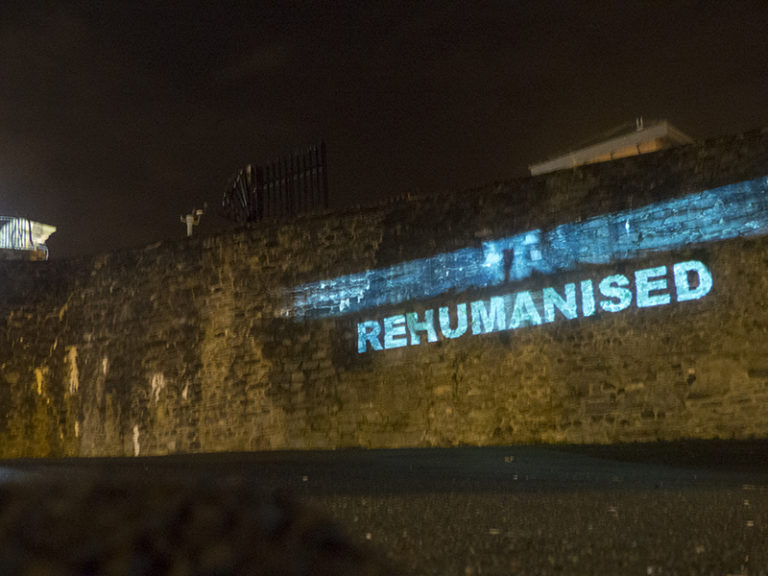

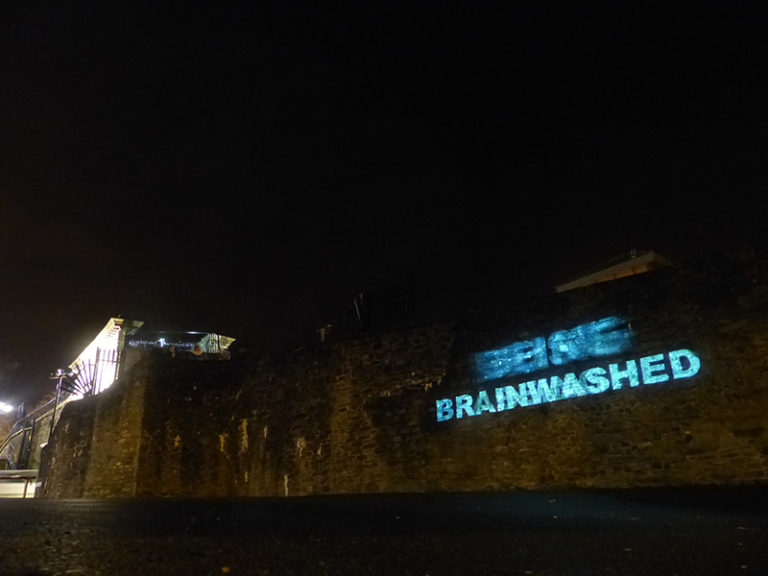

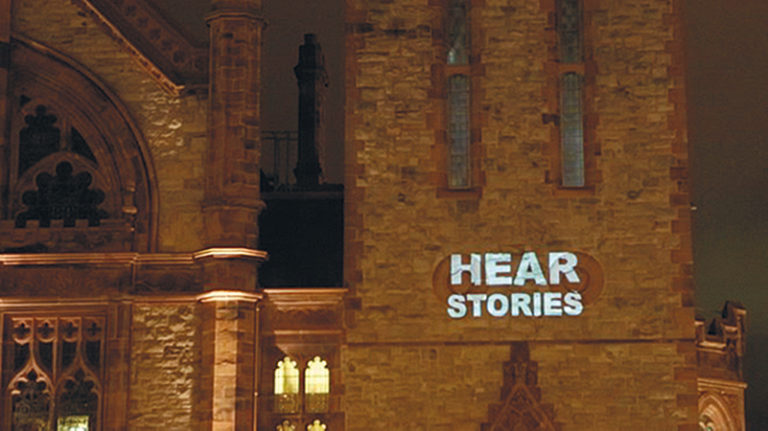

The projection dealt with local community issues and the impact of long-term political conflicts on today’s city, the life of its inhabitants, and their hopes for the future. The artist used the voices of 24 persons: ex-cops, crime victims, former detainees from both sides of the political divide, and young people whose growing up echoed the conflicts tearing

up Northern Irish society. Their voices resounded from an ambulance converted into

a projection vehicle, and the texts of their testimonies were projected onto buildings in various parts of the city.

The projection, created in partnership with the Verbal Arts Center, was part of the Lumiere

festival, commissioned by City of Culture 2013 and produced by Artichoke.

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Homeless Projection. Place des Arts, Montreal, Quebec, 2014

In this site-specific large-scale projection, the voices and bodies of homeless people frequenting downtown Montreal filled the multi-tiered façade of Théâtre Maisonneuve.

Working closely with St. Michael’s Mission and other community organizations, Wodiczko offered the homeless a space to share their experiences, tell their stories, express their fears and desires. Situating the staged projection on a theater building meant that its participants became both spectators of official culture and actors playing in their own theater, following their own lived scripts. Giving voice to marginalized persons, the artist included their narratives in the city’s public discourse.

Projection organized as part of La Biennale de Montréal, co-produced by the Musée d’art ontemporain de Montréal, the Quartier des Spectacles, and the Phi Centre, in collaboration with St. Michael’s Mission.

Krzysztof Wodiczko, John Harvard Projection

Harvard Yard, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2015

In the projection, the stone statue of John Harvard, the clergyman to whom America’s oldest university (originally a college) owes its name, “spoke” with the voices and gestures of students. Their comments were often critical of the university’s present-day policies.

Projection organized by the Harvard University Committee on the Arts (HUCA).

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Projection on the Hirshhorn Museum, 2018

Commodity in the 1980s.

The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden announces the restaging of the large-scale outdoor projection “Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, D.C.” by artist Krzysztof Wodiczko.

The first projection by Krzysztof Wodiczko on the Hirschhorn Museum was presented for three consecutive nights (25–27 October 1988) in the week prior to US presidential elections. The artist chose the wall of the museum facing an avenue (the National Mall) connecting the George Washington Obelisk with the Capitol. The projected images organically inscribed themselves in the architectural structure of the cylinder-shaped modernist building. Two hands with shirt cuff s and the cuffl inks visible seemed to embrace the museum’s spherical bulk. On one side was a hand with a straight-pointed gun, on the other a hand holding a lit candle. Both representations referred to the campaign rhetoric of the Republican candidate, George Bush, who was both in favor of death penalty and against abortion, spoke both of doing good and of people of good will (“a thousand points of light”) and of the need of militarist policies. Projected between the hands and below the bright opening of a horizontal window was the image of a row of microphones, which could evoke the notion of media “weapons” used in campaign battles.

Projection in 1988 was organized by Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden as part of the exhibition series Works (curator: Phyllis Rosenzweig). 30 years after the projection is presented as part of exhibition „Brand New” Art and Commodity in the 1980s.

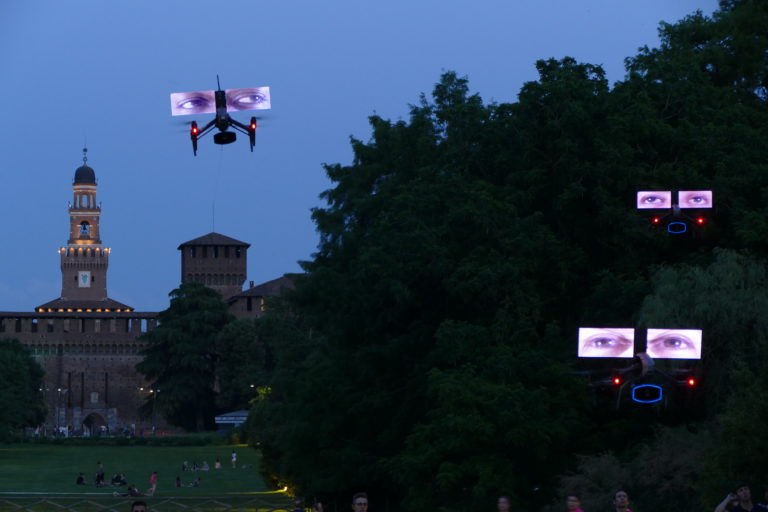

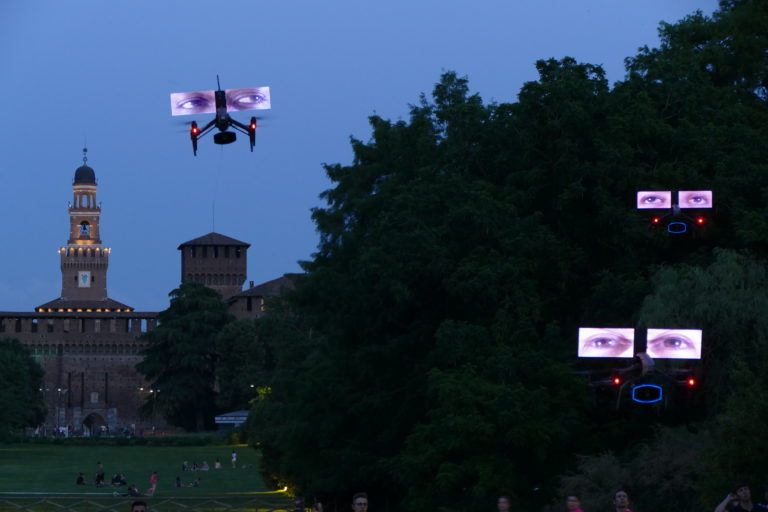

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Loro (Them) in Parco Sempione. Milan, 2019

2019

Loro (Them), Parco Sempione, Milan

Krzysztof Wodiczko worked closely with members of Milan’s growing immigrant population to explore the complexities of life as a refugee on a continent that is increasingly hostile towards foreign newcomers. The technologically pioneering installation was launched during Milan Photo Week and feature several drones flying over the city center, projecting both image and sound to audiences below. During the live performance, a swarm of customized drones carrying LED screens and amplified sound implicated the public in a series of intimate debates led by immigrant Milanesi. The eyes and the voice of the airborne machines belong to a cast of migrants ranging in immigration experience, national origin, and age.

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Monument, Madison Square Park, 2020

2020 Monument, Madison Square Park, New York

Krzysztof Wodiczko collaborated with twelve resettled refugees to the United States. Their filmed likenesses and spoken narratives are superimposed as a twenty-five minute video projection onto the 1881 monument to Admiral David Glasgow Farragut,

His personnage, a bygone symbol of naval prowess was updated and transferred to individuals not regularly honored in public monuments. With footage of people from Africa, Central America, South Asia, and the Middle East, the bronze monument emerges as a surrogate for those whose harrowing journeys and quest for democracy brought them to the United States. Monument invites the public to acknowledge a conflicted history of accepting and rejecting refugees, asylum seekers, and immigrants.

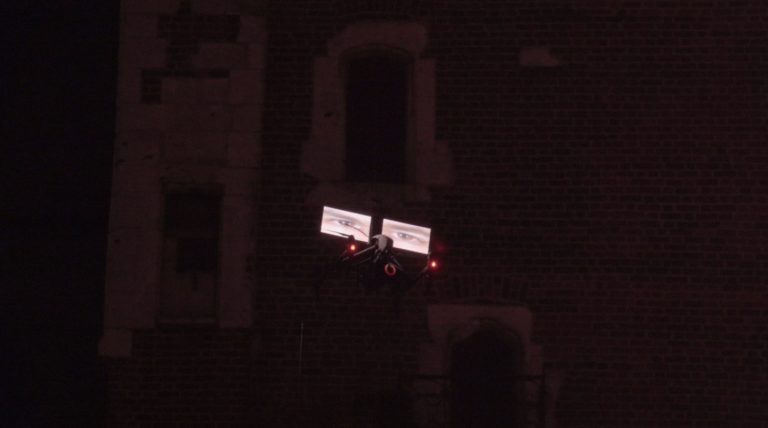

Krzysztof Wodiczko, The Sky Above Krakow. LGBT Speaks Out, Main Market Square, Krakow, 2021

2021 The Sky Above Krakow. LGBT Speaks Out, Main Market Square, Krakow

‘The project is an artistic attempt to give a public voice to person from LGBT communities. It takes advantage of drone technology. The drones are equipped with pairs of LED screens and megaphone speakers. The screen display the movements and expression in the eyes of the individuals speaking. Their eyes have been recorded simultaneously with their voice to be synchronically broadcast from the drone megaphone.

This is important because the look in the human eyes reveals, emphasizes, and accentuates the meaning of what is being said. The screens become the person’s eyes and the megaphones become their mouths. The drones acquire the character of human beings.’

Krzysztof Wodiczko, 2021

Krzysztof Wodiczko – Freedom: Above-Ground Dialogue, Gdańsk Shakespeare Theatre roof terrace, Gdańsk

“Conversations with researchers of the social situation taught me about alienating aspects of city life, such as:

– social breakdown, hostility, lack of willingness and ability to listen to the position and understand the experience of your adversary,

– prejudice against your adversary based on your simplistic perception of them in terms of narrow party, class, generational and cultural identity frameworks,

– living in an isolated bubble and locking yourself into confirming your political clichés (saying and hearing only what has been established as ‘truth’ by your group). Conversations and thinking spelt out in political echo chambers, an Anglo-Saxon term popular today: listening to your own political echo.

All these aspects of division, social fragmentation, and alienation are true for Gdańsk residents and Poles but also, to a large extent, societies all over the world.

Fostering dialogue based on attempts to listen and talk openly and without prejudice is an urgent and difficult matter. We need initiatives to seek and find common themes, experiences and needs while being open to differences and disagreements in their interpretation across party, ideological, generational, and economic divides.

I consider the attempts to create media conditions and performative situations for this purpose among the most important tasks of today’s art.

While visiting the European Solidarity Centre and the Shakespeare Theatre, it occurred to me to propose, together with the ŁAŹNIA Centre for Contemporary Art, that these institutions collaborate on a special artistic and media project in the form of an experimental contribution to this task.

The Solidarity social movement appears to be a key critical reference and tradition for attempts to create new methods and conditions for dialogue against social alienation and artificial political divisions.

The Shakespeare Theatre and its interactive tradition (e.g., allowing the contact between spectator and actor) can also inspire the creation of new anti-alienating situations and performative-media methods and techniques towards an open dialogue.

Dialogue is fostered by the ‘safe’ conditions for speaking and listening not directly, but through devices/artefacts, through a media kind of mask/megaphone to communicate and exchange experiences and views in the public space as a democratic and politically ‘exterritorial’ stage.

The air, above-ground or ‘above-Earth’ space of the city seems just such an extraterritorial stage for a potential dialogue between alienated people.

The projection on the hovering screen-balloons would function as a communicative mask through which the above-ground, nearly angelic, aerial dialogue would be easier to imagine and carry out.

I think that this dialogue, previously initiated and started ‘on the ground’ as preparatory dialogue workshops, could also be continued and developed during the performance.

Interested spectators could become its co-participants.

Their spontaneous reactions and utterances ‘from the ground’ would be transmitted and incorporated in real time into the ongoing conversations as an improvised addition and organic part of the above-ground dialogue”.

Krzysztof Wodiczko on his work on the project Freedom: Above-Ground Dialogue