Krzysztof Wodiczko, The Power Plant

University of Toronto, 1980

Confederation Centre of the Arts

Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, Canada, 1981

Krzysztof Wodiczko, School of Architecture, Dalhosuie University of Nova Scotia, Halifax, Nova Scotia,, 1981

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1981

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Scotia Tower, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1981

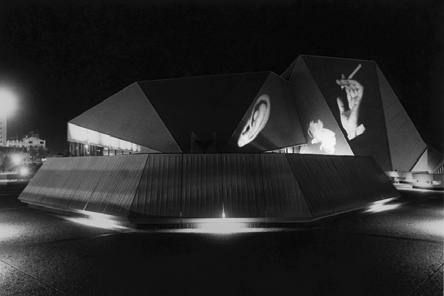

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Qantas Interantional Centre, Sydney, 1982

Organized for the 4th Biennale of Sydney

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Mutual Life and Citizens Assurance Company Centre Tower, 1982.

Organized for the 4th Biennale of Sydney

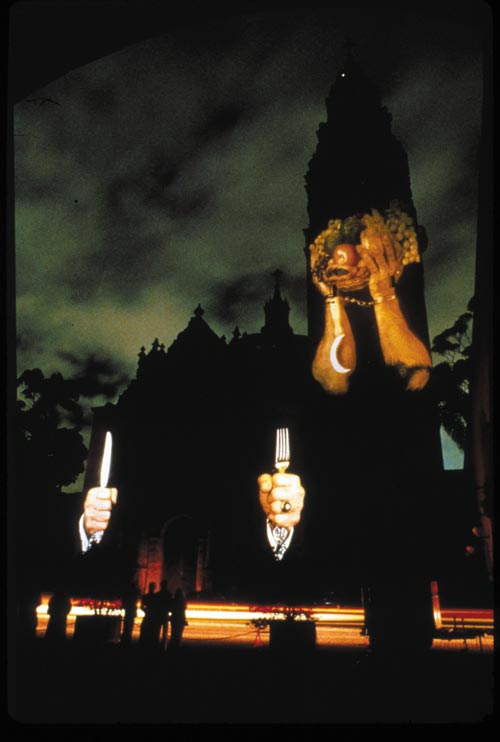

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1982

The projection was presented for two nights during the opening of the 4th Biennale of Sydney. The projected

images alluded to the ambiguity of the functioning of artistic institutions, on the one hand operating the

discourse of openness, on the other — authoritarian and entangled in systems of authority. The projection’s

main motif were alternating images of closing and openings hands projected on the walls of the gallery’s side

wings. On the sides of the main-entrance portico images of ears were projected, and on the fronton above the

entrance, the image of angrily knitted eyebrow. The projection was an expression of support for Australian

artists demanding legal regulations (contracts) for their participation in the Biennale.

organized for the 4th Biennale of Sydney

artist’s assistant: Ian de Gruchy

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Festival Centre Complex, 1982

The projection transformed the campus buildings into images of corrugated-steel tents resembling shacks built by impoverished Native Australians. It took place on the site of a former native village, destroyed two hundred years earlier by British colonists. It was carried out according to the artist’s script as he himself wasn’t present. organized by the Adelaide Festival

Krzysztof Wodiczko, War Memorial, 1982

Organized by the Adelaide Festival and the South Australian School of Art, Adelaide in conjunction with the exhibition Poetics of Authority: Krzysztof Wodiczko at the Gallery of the South Australian College of Advanced Education

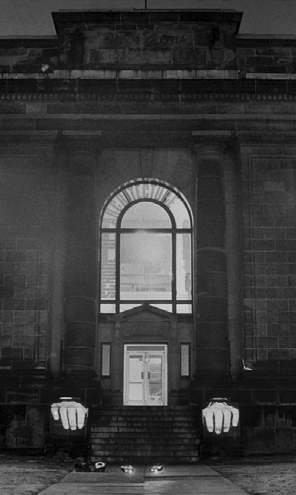

Federal Court House, London, Ontario, 1983.

The projection took place on the modern federal court building. Images of fi sts clenched on iron prison bars were projected on the front walls of the building’s side wings housing cells for detainees awaiting trial. organized by the Greater London Art Gallery

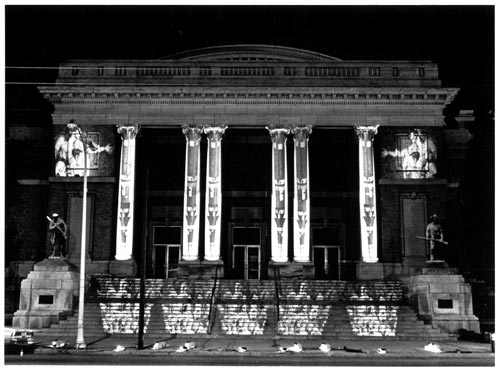

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Memorial Hall, 1983

With the projection in Dayton, the artist changed the meanings evoked by the commemorative iconography of a building erected in the early 20th century to commemorate soldiers fighting in the US civil wars and the US-Spanish war. The relationship between the projected images and the neo classical architecture produced a highly critical reading of history and the ways of remembering it. The portico’s columns became missiles pointed downwards, towards the image of a crowd gathered on the stairs leading up to the building. On both sides of the columns, in the place of inscriptions honoring those who died for their country, the artist projected identical, symmetrically arranged, images of lamenting mothers borrowed from Jacques-Louis David’s painting The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons. The lamenting motif highlighted the patriarchal ethos of war inscribed in the monument, erected in the memory of soldiers who died defending Montgomery County, home of the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, one of the largest such bases in the US.

Projection was part of the Art in Public Places program organized by City Beautiful Council and Wright State University with the assistance of students from the Art Department, Dayton.

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Hauptbahnhof, Sttutgart, 1983

The site of the projection was the city’s main train station building, a monumental stone structure completed

in 1927 to the design of Paul Bonatz. The artist projected the image of two folded hands on a side wall of the

clock tower, the dominant feature of this part of town. A business executive’s manicured hands in elegant

cuff s corresponded with the Mercedes-Benz logo on top of the tower. The projection was held at a time when

the company, operating the city’s largest industrial plant, employed particularly many ‘guest workers’, or Gastarbeiter. Stuttgart, an important railway junction, was an infl ux point for immigrants searching for work and gathering around the train station. The second part of the projection, which was to show the hands of the Gastarbeiter carrying their travel bags, didn’t take place due to fi nancial reasons.

The projection, organized by the Württembergischer Kunstverein, Stuttgart in conjunction with the exhibition Künstler aus Kanada: Räume und Installationen, was presented two nights a week for the duration of the exhibition

curator: Tilman Osterwold

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Jubilee Column (Jubiläumssäule), Schlossplatz, Stuttgart, 1983

The projection coincided with parliamentary elections in West Germany, during which the Christian Democrats

(CDU) pledged to deploy nuclear-capable Pershing 2 ballistic missiles around all large German cities. The

CDU’s offi cial agenda at the time suggested peace could only be achieved through muscle. An inscription to

similar eff ect can be found on the 19th-century Jubilee Column erected to mark the 25th anniversary of the

reign of King Wilhelm I and situated at the centre of the baroque Schlossplatz. The artist projected an image

of the missile on the 30 meter-tall column crowned with a Concordia statue, the image becoming a base for the

goddess of Agreement and Harmony holding a laurel wreath and palm leaves.

The projection was realized without permission from the city, it was not supported by the Württembergischer

Kunstverein in Stuttgart and was not part of the show Künstler aus Kanada: Räume und Installationen in which

the artist participated.

The projection was produced with the help of artists from the Künstlerhaus in Stuttgart

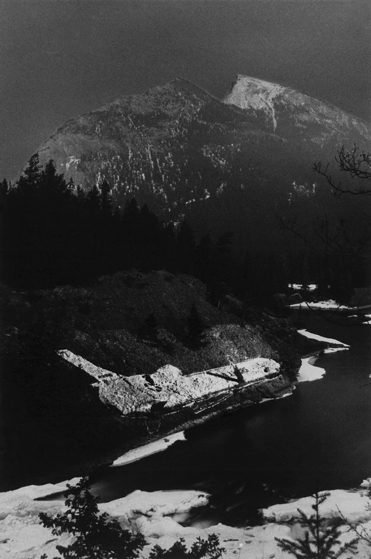

Krysztof Wodiczko, Bow Falls, Banff, Alberta, Canada, 1983

Held in a natural setting, in the oldest national park in Alberta, in the Rocky Mountains, near the popular tourist town of Bow Falls, the projection was unique for the artist’s work usually involving buildings or manmade monuments. This time too, however, Wodiczko used a motif characteristic for his 1980s projections; in a canyon, on a rocky river bank, the image of a missile, magnifi ed several times, was projected. At the time when the projection took place, the Canadian public opinion was protesting against the decision to test Cruise missiles in Alberta, which the government said made sense because the province had a similar lay of the land as Siberia.

organized by The Banff Center

assistance: Brian McNevin

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Museum of Natural History, Regina, Saskatchewan, 1983

The projection referred critically to the patronizing modes of collecting other cultures and to museum discourses constructed exclusively from the viewpoint of Western history. On the central part of the building, which houses a collection presenting the history of the First Nations, the artist projected an image of the (white) cerebral cortex, in what was an ironic reference to the sculptures of white settlers adorning the side wings.

Organized by the Regina Art Gallery

Krzysztof Wodiczko, South African War Memorial, Toronto, Canada, 1983

The projection went forward despite the lack of police permission for its presentation. It was interrupted by the police two hours later.

Organized by the Ydessa Art Foundation, Toronto in conjunction with the artist’s solo exhibition

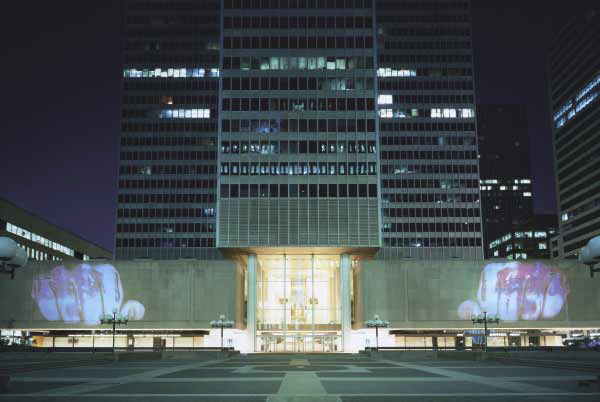

Krzysztof Wodiczko, At&T Long Lines Building, New York, 1984

On 2 November 1984, two days before US presidential elections, Krzysztof Wodiczko carried out a projection

on a building in Lower Manhattan, New York’s fi nancial district. On the north wall of the 40-fl oor high-rise,

the artist projected a huge image of a hand held horizontally in a swearing-in gesture. But while in the actual

swearing-in ceremony the hand is directed towards the heart, here is was “pressed” against the building (main

offi ce of the AT & T corporation), symbolically reaching out towards the voters and future addresses of the

president-elect’s oath. The hands image had been sourced from a photograph of Ronald Reagan.

organized by The Kitchen Performing Arts Center, with assistance of the Lower Manhattan

Cultural Council

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Astor Building/New Museum, New York, 1984

“It was winter and I was living very close to the main shelter for homeless men and quite close to a shelter for

women. I saw many people living on the street, trying to survive the bitter-cold temperatures by burning tyres.

It was therefore shocking to me to see one of the largest buildings in the entire neighborhood empty. It was

very evident that the building that houses the New Museum was completely dark. People speaking to me at the

time of the projection had no doubts whatsoever about the meaning of it. I learned that the upper fl oors of the

building were awaiting new tenants at a price nearly one million dollars each and at the same time the New

Museum received the basement and ground fl oor spaces for free, or at least for a very cheap rent. The very fact

the museum moved into the buildings creates a certain myth for the building. There are, in fact, two exhibition

spaces there. One is for the New Museum exhibitions, and next door there is an exhibition of the former state

of building and how it will look after renovation, a real-estate exhibition. There is obviously a connection

between the presence of the museum and the subsequent conversion of the entire surrounding area into one

of art galleries and other art-related institutions and business. I’m not saying that there is a direct responsibility

on anyone’s part, but this is a mechanism and it’s important to recognize and reveal our place within that

mechanism, even if we cannot change it at this point.”

“Conversation with Krzysztof Wodiczko,” with Douglas Crimp, Rosalyn Deutsche, and Ewa Lajer-Burcharth,

October, no. 38 (Winter 1986), p. 43.

Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch

Grand Army Plaza, Brooklyn, New York, 1984/85

The projection was part of the New Year’s celebrations with fi reworks and music concerts organized

annually by the Borough of Brooklyn for the local community. On New Year’s Eve 1984, Krzysztof

Wodiczko projected on the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch an image of two missiles connected by

a chain. The representations, of a US missile and a Soviet missile, were used in the context of planned

arms reduction talks between the United States and the Soviet Union. Visible above the image of the

padlock linking the chains, projected on the arch’s keystone, was a statue of freedom, a winged Victoria

crowning the arch from the south.

“This is a monument to the Northern army, so the south side of the arch is very busy with representations

of the army marching south to liberate the South from ʻwrongdoing.ʼ The monument has absolutely

nothing to say about the North, because if it did it would have to refl ect on itself . . . Ironically, this

arch, which is victorious Northern army and which uses the typical classicizing Beaux-Arts style in the

work of [Augustus] Saint-Gaudens, is challenged by two small, realist bas-relief sculptures by [Thomas]Eakins placed inside the arch. They are the only two fi gures actually walking north, coming back from

the war, extremely tired. As far as I know, this is the only monument in the world that contains such an

internal debate, aesthetically and historically. . . . The people viewing the projection off ered their own

interpretations. What I liked was that everyone was trying to impose his or her reading the symbols and

referring to the contemporary political situation. It was a time when the public was being prepared for impending peace talks between the US and Soviet governments. There were great expectations about

coming back to the conference table and perhaps for a reduction of the arms race. . . . Because the debate

was open and easily heard, all the readings were most likely received by everyone, and hopefully this

social and auditory interaction helped the visual projection survive it the public’s memory as a complex

experience. For a moment at least, this ʻnecro-ideologicalʼ monument became ʻalive.ʼ”

“Conversation with Krzysztof Wodiczko,” with Douglas Crimp, Rosalyn Deutsche, and Ewa Lajer-Burcharth,

October, no. 38 (Winter 1986).

organized by the Prospect Park Administrator’s Office, New York City Department of Parks and Recreation

curator: Mariella Bisson, Art-in-the-Park Program

Conference Center of the Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, 1984

Organized by Ohio State University in conjunction with International Conference of Humanities

on George Orwell’s 1984

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Tower Gallery, Nowy Jork, 1984

Organized in conjunction with the exhibition Body Politics at the Tower Gallery

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Seattlle Art Musem, Seattle, 1984

The projection was a critical examination of museum institutions with their ability to hide their collections.

On the two wings of the museum building (today the Seattle Asian Art Museum), the artist projected images

of fi le cabinet handles, transforming the 1930s modernist structure into a cabinet with two solid, tightly closed

drawers. Emphasizing the non-accessibility of the museum archive, the artist refl ected critically on the archiving

practices of the systematization and isolation of collective memory.

Organized in conjunction with the exhibition Public Comments at the Seattle Art Museum

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Nelson’s Column, Trafalgar Square, Londyn, 1985

In the center of London’s Trafalgar Square, on the shaft of a tall column topped with a statue of Admiral

Horatio Nelson, the image was projected of a large, intercontinental ballistic missile, wrapped in barbed wire.

Simultaneously, images of tank tracks were being projected on the plinths of the four bronze lions surrounding

the column.

Organized by the Institute for Contemporary Art and The Artangel Trust in conjunction with the artist’s solo exhibition at Canada House, London

curator: Declan McGonagle

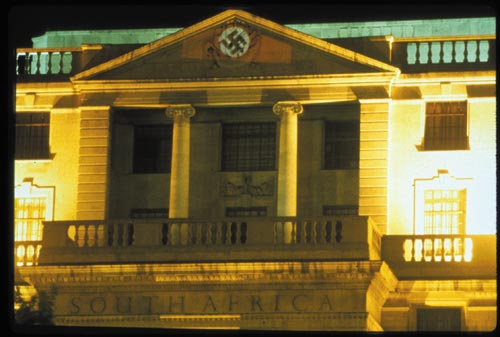

Krzysztof Wodiczko, South Africa House London, 1985

It was an improvisation during the projections on Nelson’s Column and the Duke of York Column in London.

One of the projectors was directed by the artist towards the South Africa House building in a gesture of support

for demonstrations against South Africa’s apartheid policies and the loans off ered to Pretoria by the Margaret

Thatcher government. On the building’s front wall with a relief of a boat and in the inscription “Good Hope”

(the Republic of South Africa national motto), the artist projected a swastika. The nearly two-hour projection

was interrupted by the police on public disturbance charges. The RSA government subsequently issued a note

of protest to the government of Canada, demanding explanations about a Canadian artist’s action against an

RSA embassy. In response, the Canadian government said individual citizens’ actions didn’t necessarily have to

refl ect the government’s offi cial position. The projection was viewed by some 2,000 people; the December issue

of Time Out proclaimed it one of the year’s most important events in London.

production coordinator: Steve White

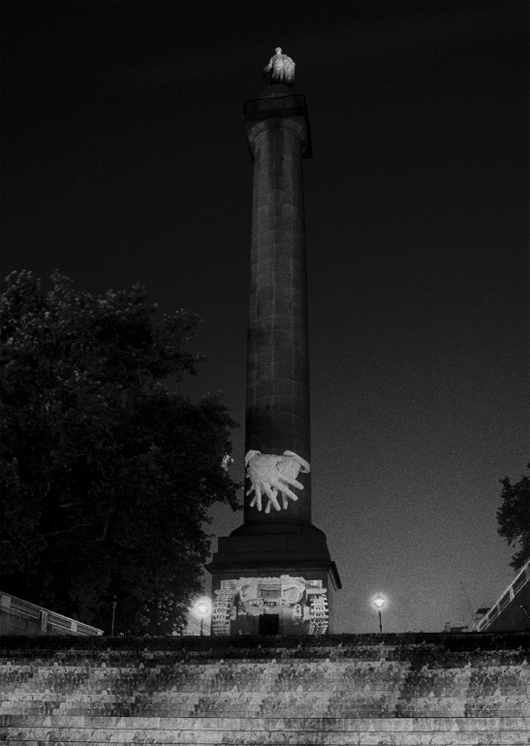

Krysztof Wodiczko, Duke of York’s Column, Waterloo Place, London, 1985

The projection, realized concurrently with the one on Nelson’s Column, followed a wave of strikes by Welsh

miners. The artist projected the image of a crowd of British miners on the stairs leading up to the column, while

an image of an armored vehicle in full speed was projected on the base of the column and that of crossed hands

on the lower part of the column itself. The projection, which took place during a “sound and light” event titled

The Heart of the Nation, commemorating crucial moments in the history of the British Empire, served as an

alternative to the offi cial, imperial symbolics and public space-decoration spectacles.

Organized by the Institute for Contemporary Art and the Artangel Trust in conjunction with the

artist’s solo exhibition at Canada House, London

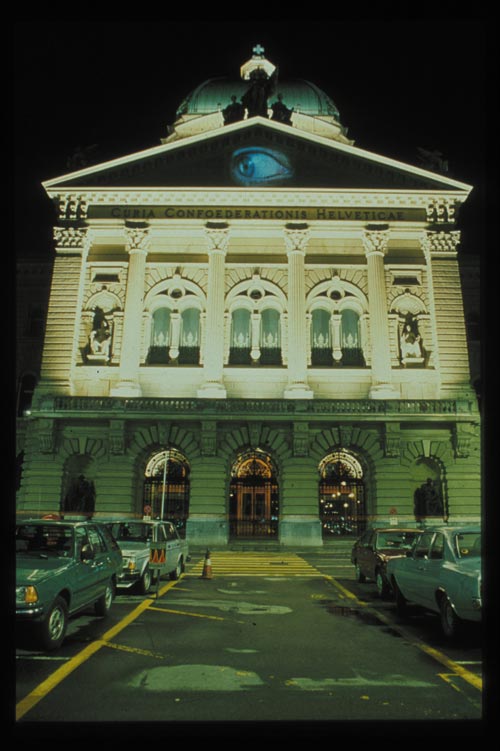

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Bundeshaus, Bern, 1985

“I knew I wanted to project onto the pendiment, since it was the only free surface on the building. It was

a question of what would be acceptable, and then, when accepted, what would make a point. I fi gured no one

would object to the image of an eye, and at the same time they wouldn’t have to know that the eye would change

the direction of its gaze, looking fi rst in the direction of the national bank, and then at the canton bank, then

the city bank of Bern, then down to the ground of the Bundesplatz, under which is the national vault containing

the Swiss gold, and fi nally up to the mountains and the sky, the clear pure Calvinist sky . . . I had spent a certain

amount of time in bars in Bern and I learned there about the Swiss gold below the parking area in front of the

parliament, a fact which most people in Switzerland take for granted. It’s not, after all, so bad to be a tourist.

Sometimes you learn things that local residents take for granted and then able to expose the obvious in

a critical manner.”

“Conversation with Krzysztof Wodiczko,” with Douglas Crimp, Rosalyn Deutsche, and Ewa Lajer-Burcharth,

October, no. 38 (Winter 1986), p. 43.

Organized by Kunsthalle and Kunstmuseum Bern, in conjunction with the exhibition Alles und noch viel mehr at the Kunstmuseum Bern

curator: Jean Hubert-Martin

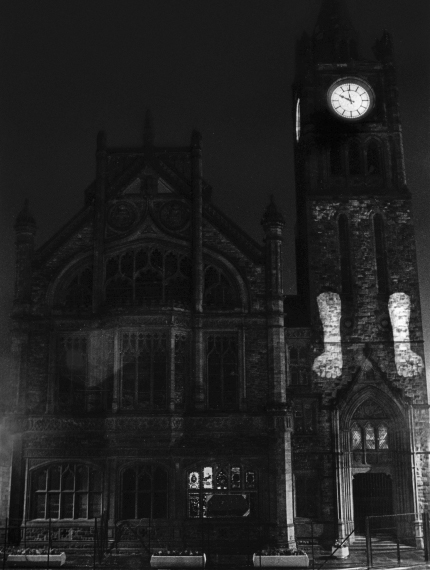

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Guildhall, Derry, Northern Ireland, 1985

“This project was on the city hall in Derry, Ireland. The building is located just in front of the city wall, which

contains cannons which are pointed at the building. The cannons, gifts from the citizens of London during the

eighteenth century, were intended to reinforce the power of the British tradition. The tower was destroyed at

one point by the IRA, by a person who was later imprisoned for this act. During his imprisonment, the political

situation changed and the Catholics gained power. The Protestants moved across the river to a stronghold in

the center of the city, protected by the British Army. The election for the city council put this guy who was still

imprisoned into offi ce. The tower was rebuild . . . It was obvious that my mission was to speak to both Catholics

and Protestants for whom there is no shared icon. In a way it was the most diffi cult projection for me to do.

The area was a battle zone . . . While I was projecting, there were seven policemen with guns around us. Why

I had to be protected, I don’t know. It became a military operation, that projection. I was not particularly shocked

by this, but it was certainly more tense than I ever remember in Poland, including 1957 or 1968, or during

seventies. It was more frightening to see how people live normally under these circumstances that they can

actually adjust to such conditions. It was so much more frightening in Ireland than in Poland because there the

situation has such a long history. People are born who don’t remember anything else. To remember something

else might be the reason for public art.”

Krzysztof Wodiczko, “Projections,” Perspecta: The Yale Architecture Journal, no. 26 (1990).

Organized by the Orchard Gallery, Derry, in conjunction with the artist’s solo exhibition

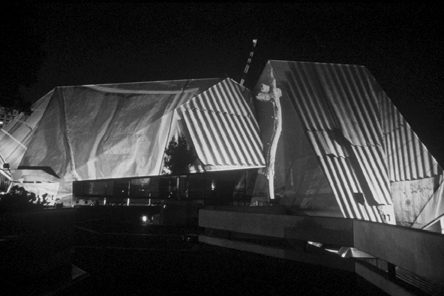

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Festival Centre Complex, Adelaide, Australia,1985

The projection transformed the campus buildings into images of corrugated-steel tents resembling shacks built

by impoverished Native Australians. It took place on the site of a former native village, destroyed two hundred

years earlier by British colonists. It was carried out according to the artist’s script as he himself wasn’t present.

Organized by the Adelaide Festival

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Royal Bank of Canada Building, Montreal, Canada, 1985

The projection took place at a time when the Royal Bank of Canada was trying to secure major deals in South

Africa while the governing National Party openly supported apartheid policies.

Organized for the Aurora Borealis Festival of Contemporary Art

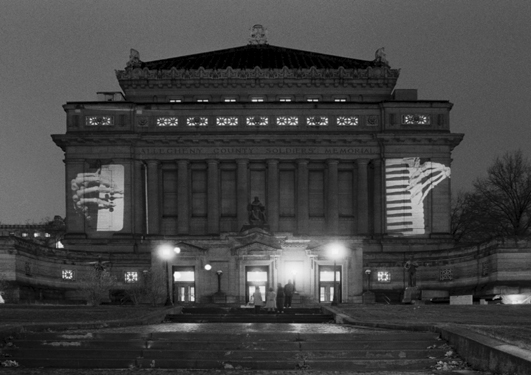

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Alegheny County Memorial Hall, Pittsburgh, USA, 1986

“All War Memorials in the United States operate as cultural sites, performing social functions for the

community of the city. In order to see music, lectures, operas, sporting events — in order, in other words,

to have access to culture, one must go through the showers. One passes through displays, environmental

arrangements of images, memorabilias, and mythical objects, like the bullet which grazed the leg of some

general on some battle. The buildings invested with neoclassic, purifying, disciplining order. It imposes through

monumental scale and all kinds of signs and symbols on its surface, such as texts related to patriotism and

commemorating all wars, without distinction, wars very democratically listed. From this point of view veterans

have an enormous forum to infi ltrate their sentimentality for war. On one hand there is this sweet sound, on the

other, cannons.

In Memorial Hall, Dayton, the imagery was from art history, from a painting about sacrifi ce and patriotism

by David, together with missiles, crowds, a whole set of separate images thrust close upon the viewer to be

connected in the tradition of montage. In Pittsburgh, one’s distance from the structure is much greater, so

images could be related to the entire building. In Dayton suggested impending disaster, Pittsburgh involved

post-disaster imagery. There is an iconographic tradition of the skeleton playing an instrument in European

popular art, the dance of death. The accordion is the most complex but portable instrument for wandering

musicians. It is also a very working class instrument and Pittsburgh — its history and memory and social

culture — is still a working class city . . .”

Krzysztof Wodiczko, in Counter Monuments: Krzysztof Wodiczko Public Projections, exh. cat. Hayden Gallery, List

Visual Arts Center (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1987).

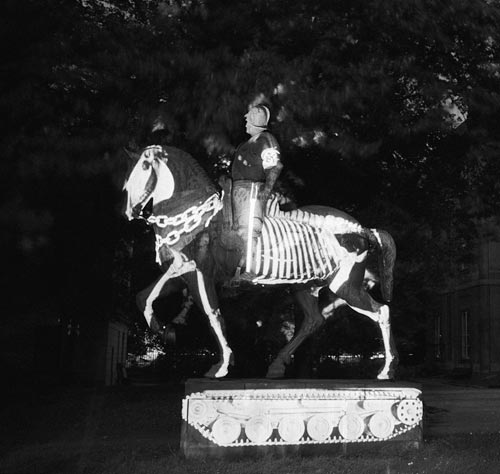

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Condottiere Bartolomeo Colleoni Statue

Academy of Fine Arts, Warsaw, 1986

The projection was carried out at a time when many of the police-state measures introduced during martial law

in Poland (1981–83) were still in force. In a reference to the 47th anniversary of the German invasion of Poland,

the artist transformed the copy of Verrochio’s statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni standing in the inner courtyard of

Warsaw’s Academy of Fine Arts into an apocalyptic rider with a swastika on his arm and a police baton.

Organized by Galeria Foksal in conjunction with the artist’s solo exhibition

Krzysztof Wodiczko, The Homeless Projection 2

Soldiers and Sailors Civil War Memorial

Boston 1986/87

In the projection on the monument erected in the memory of the protagonists of celebrated history, the artist

showed images of anti-heroes, people unrepresented in the offi cial version of history. A monument to Civil

War soldiers was transformed into a monument of homeless people and their fi ght for survival. At the foot

of the monument, from four sides, images of homeless people, surrounded by their typical accessories such

as shopping trolleys or plastic bags fi lled with bottles and cans, were projected. On the column above was

projected a photographic image from the construction of one of Boston’s residential buildings, showing the

logo of the developer, the Turner Construction Company, in what was a clear allusion to a connection between

real-estate development and rise in homelessness. Like Wodiczko’s other monumental projections, The Homeless

Projection 2 revealed what offi cial monuments try to deny.

Organized as part of the First Night New-Year festival, it was viewed by over 200,000 people.

The Venice Projections

As part of the 42nd Venice Biennale, Krzysztof Wodiczko, representing Canada, carried out four projections

in various places around the city: the Condottiere Bartolomeo Colleoni Monument at Campo Santi Giovanni

e Paolo, the St. Mark’s Campanile at Piazza San Marco, the Porta Magna (the main gate to the Arsenal), and

on the façade of the church and bell tower at Campo Santa Maria in Formosa. In the projected images the

artist combined attributes alluding to the wealth of the former Venetian Republic and the city’s contemporary

economies based on mass tourism with military motifs referring both to Venice as a former colonial power

and to its present-day situation: the threat of terrorist attacks and the resulting prospect of a slump in the

tourist industry.

Organized by the Canadian Pavilion, 42nd Venice Biennale

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Fine Arts Center, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, USA, 1986

The projection took place at a time when MIT students were protesting against the academy’s participation

in military-related research programs. The artist projected photographic images of missile models of his own

making on the Fine Arts Center building.

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Monument to Friedrich II, Kassel, Niemcy, 1987

“On the monument to Landgrave Friedrich II of Hesse-Kassel, I confront his glorious but also egomaniacal

heroic acts — the spreading of ideas of the Enlightenment and the popularizing of aristocratic culture, the

promotion of art and science — with his dubious economic and political acts, which served as the monetary

source for all of his cultural and artistic projects. His politics, incidentally, were a source of criticism even his

life time. Gazing proudly at one of these projects, the Museum Fridericianum, his obscene white body too

bloated from gluttony to fi t its heroic Roman armor, the Landgrave cannot conceal his ravenous hunger for

conquest, his imperial appetite for plundering foreign territories (look at Austria). He is interested in political

and cultural power over the world. (One thinks about Polish crown.) He also knows that Soldatenhandel, a trade

in soldiers in the eighteenth century (22,000 peasants were sold to Great Britain for 21,276,778 talers in order

to support that country’s war against American independence), is hardly diff erent from Daimler-Benz’s use of

slaver labor today by exploiting ‘guest workers’ to make military equipment such as the Unimog S (a four-wheel-

-drive military truck, parts of which are produced in Kassel) and deliver it to South Africa, where it is used to

subjugate blacks; or from accepting donations from Mercedes and the Deutsche Bank, though knowing of their

South African dealings, in order to organize Documenta 8 in the Fridericianum and the Orangerie Gardens

— places Friedrich II built with money from the trade in soldiers. To expose the relation between Daimler-

Benz and Documenta 8 as a clear example of the way the shameless “history of the victors” perpetuates itself

today, I had decided to recall the Landgrave’s monument in order to critically actualize it. This slide projection superimposed onto the large base of the monument an image of a crate containing axles to Unimog S military

trucks produced by the Daimler-Benz plant in Kassel. The content, the manufacturer, the origin, and the South

African, Salvadoran, and Chilean destinations of this shipment were clearly marked on each side of the crate.

The statue itself was subjected to similar superimposition. Projected over his Romar armor, a white shirt, tie,

and Daimler- Benz identity badge had transformed the Landgrave into both warrior and company executive. The

face of Friedrich II, which according to many spectators resembled that of the Documenta 8 director, as well as

tubes held by the statue containing architectural and cultural designs, were both strongly illuminated.”

Krzysztof Wodiczko, in Documenta 8, vol. 2, exh. cat. (Kassel: Fridericianum, 1987), pp. 278–79.

Organized for Documenta 8, Kassel

curator: Manfred Schneckenburger

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Martin Luther Kirchturm

Kassel, 1987

The projection of the image of a man in a mask and protective overalls alluded to the contemporary risks caused

by chemical pollution and radioactive waste. The fi gure, its hands joined in a gesture of prayer, inscribed itself

in the soaring architecture of the neo-Gothic church. The tower of the former Lutheran church, the city’s tallest,

is one of the few buildings in the city that survived the Allied bombing raids at the end of World War II. Half

a year before the opening of Documenta 8, an evacuation alert was sounded in Kassel for the fi rst time since the

end of the war, the reason being a possible pollution hazard from industrial plants in Leipzig and Frankfurt.

Organized for Documenta 8, Kassel

curator: Manfred Schneckenburger

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Westin Bonaventure Hotel, Los Angeles, USA, 1987

The projection took place at a super-modern shopping plaza located in downtown Los Angeles. Regarded as

a symbol of global capitalism, the Westin Bonaventure Hotel, built in 1976 to the design of John Portman,

comprises fi ve cylindrical steel-and-glass structures 367 feet tall, housing a large atrium with fountains and

swimming pools. The luxury hotel, the city’s largest, described by Fredric Jameson as a key example of the

“logic of late-capitalist culture,” often compared to an inaccessible stronghold, is closely guarded. On the wall

of a concrete podium blocking access to the hotel the artist projected images of misery and enslavement,

contrasting with the surroundings and usually kept away from big-city streets.

Organized by the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Museum Fridericianum, Kassel, Niemcy, 1987

The projection took place on the Museum Fridericianum, founded by Frederick the Second of Hessia as

Europe’s fi rst public museum, where today the exhibitions of the successive editions of Documenta are

presented. On the tympanum of the neo-classical building, the artist projected the image of an eye, alluding

ironically both to Eye-of-Providence symbolism and to art’s dependence on “providential” sponsors, such the big

corporations subsidizing Documenta and known for their fi nancial dealings with the South African regime.

Organized for Documenta 8, Kassel

curator: Manfred Schneckenburger

Krzysztof Wodiczko, The Border Projection, 1988

The project comprised two projections carried out on two consecutive nights on two sides of the US-Mexican border,

in San Diego, USA, and Tijuana, Mexico, two cities forming a large conurbation separated by the national border, crossed here by more illegal immigrants than anywhere else. In both cities the projections took place on buildings symbolic for their tradition and history.

The San Diego Museum of Man

The architectural complex today housing The San Diego Museum of Man was erected in 1915–16 for the purposes of the Panama-California Exposition, organized on the occasion of the inauguration of the Panama Canal. Designed in a colonial, richly decorated style, the buildings were to highlight San Diego’s Spanish heritage. The ornamented façade of the Californian Building, full of patriotic and ecclesiastic references to the colonial past, with fi gures of kings, conquistadors and martyrs, was the site of the projection, which highlighted the reverse side of the triumphal history of colonialism. On both sides of the main entrance the artist projected images of manicured hands holding elegant cutlery, while on the soaring tower nearby was projected the image of work-worn hands embracing a large fruit basket. The juxtaposition of jewellery-adorned hands and elegant shirt cuff s, on the one hand, and fettered hands and a knife used for picking fruit, on the other, problematized the glorifi cation of the colonial past.

Organized by La Jolla Museum of Contemporary Art in conjunction with the artist’s solo exhibition

curator: Madeleine Grynsztejn

Krzysztof Wodiczko, R. C. Harris Walter Filtration Plant

Toronto, 1988

The projection, which showed a crying public official signing a document over a glass of water and a dead fi sh, referred to issues related to water management in the Canadian province of Ontario. During a period of prolonged drought in North America, the Canadian House of Commons was close to signing a free trade agreement with the United States. Part of the negotiations were requests by some US states for the right to draw water from the Great Lakes to alleviate shortages caused by the drought, which threatened to lower water levels to a critical point.

Organized by Visual Arts Ontario in conjunction with the exhibition WaterWorks

Krzysztof Wodiczko, National Monument

Calton Hill, Edinburgh, 1988

The projection, carried out for ten consecutive nights during the Edinburgh Festival, took place on the city’s

Calton Hill, where a monument stands commemorating soldiers who died fi ghting for the British crown in the

Napoleonic wars. Due to the fact that it was never completed, the 19th-century National Monument, modeled

on the Parthenon in Athens, has also been called a “monument of shame.” On its Doric columns, the artist

projected images of homeless people seemingly supporting the Latin inscription on the entablature: “Morituri te

salutant” [Those who are about to die salute you]. Opposite the monument, on the dome of the New Observatory

building, the image was projected of the face of Britain’s then prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, and on the

entablature above the columns of the portico leading to the Observatory, the inscription “Pax Britannica.”

Organized by Artangel Trust, London and the Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, for the Edinburgh

Festival

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, DC, 1988

The projection was presented for three consecutive nights (25–27 October) in the week prior to US presidential

elections. The artist chose the wall of the museum facing an avenue (the National Mall) connecting the

George Washington Obelisk with the Capitol. The projected images organically inscribed themselves in the

architectural structure of the cylinder-shaped modernist building. Two hands with shirt cuff s and the cuffl inks

visible seemed to embrace the museum’s spherical bulk. On one side was a hand with a straight-pointed gun, on

the other a hand holding a lit candle. Both representations referred to the campaign rhetoric of the Republican

candidate, George Bush, who was both in favor of death penalty and against abortion, spoke both of doing good

and of people of good will (“a thousand points of light”) and of the need of militarist policies. Projected between

the hands and below the bright opening of a horizontal window was the image of a row of microphones, which

could evoke the notion of media “weapons” used in campaign battles.

Organized by Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden as part of the exhibition series Works.

curator: Phyllis Rosenzweig

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Flakturm

Arenberg Park, Vienna, 1988

The project was a response to the controversies caused by the publication of news about the past of the then

Austrian Chancellor, Kurt Waldheim, concerning his membership in the SA and service in the Wehrmacht

during World War II. Projected on a former bunker built by the Nazis was the image of a large hole through

which a fragment of a horse’s white rump could be seen. The white horse, a popular image in Austrian

iconography, was an allusion to Waldheim’s membership in the Nazi horse-riding association and to an ironic

comment by an Austrian member of parliament that if Waldheim was innocent, then perhaps it was the horse

that was guilty.

Organized by the Wiener Festwochen

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Neue Hofburg, Heldenplatz, Vienna, 1988

The projection, organized in connection with the Flakturm one, took place on the 50th anniversary of the Third

Reich’s annexation of Austria. The artist chose one of the Hofburg’s fi nest buildings, from the balcony of which

Hitler in 1938 announced the Anschluss and near which, in one of the wings, the chancellery of the President

of Austria is located. On the front wall of the Neue Hofburg building, the artist projected a huge image of an

eagle’s spread wings, photographed in the nearby Natural History Museum, which brought to mind the German

national emblem of the Third Reich era. In the centre, between the eagle wings superimposed on the wings

of the building, was projected the logo of Noricum, an Austrian arms producer specialising in long-distance

missiles, which during the Iraq-Iran war, taking advantage of Austria’s neutral status, sold weapons to both sides

of the conflict.

Organized by Wiener Festwochen

curator: Catherine Pichler

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1989

The projection took place at a time when in the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev had initiated democratization

processes known under the collective name of glasnost (transparency), whereas in the United States, on the

initiative of Senators Jesse Helms and Alphonse D’Amato, a debate had started on the censorship of artistic

activities subsidized by the federal government, as a result of which the National Endowment for the Arts

introduced more restrictive policies and stopped supporting art criticized by the conservatives. On the Marcel

Breuer-designed Whitney Museum building, America’s fi rst museum for collecting art by living artists,

Wodiczko projected the images of two open hands, one with the word “Glasnost,” the other with the words

“In USA.” The projection was a response to the unconstitutional attempts to restrict freedom of speech

promoted at the time by conservative politicians.

Organized by the Whitney Museum in conjunction with the exhibition Image World: Art and Media Culture

curators: Marvin Heiferman, Lisa Phillips, and John G. Hanhardt

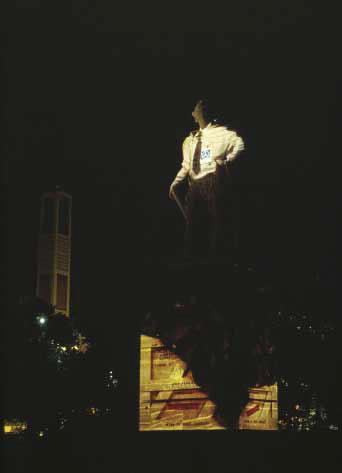

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Lenin Monument

Leninplatz, Berlin, 1990

As part of the exhibition Die Endlichkeit der Freiheit, organized shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Krzysztof

Wodiczko carried out two parallel projections, one in the former East Berlin, the other in what used to be West

Berlin.

In the Leninplatz projection, the artist transformed the Russian revolutionary into a Polish tourist, dressed in

a striped shirt and pushing a supermarket trolley fi lled with cheap household electronics. The representation

of the communist leader laden with consumer goods, products of the bugaboo of consumerism, was an ironic

image of the ultimate end of the proletarian utopia. In his reinterpretation of the monument, Wodiczko replaced

the monumental heroization of a cult fi gure of Soviet power with the image of an anti-hero, as unwelcome in the

former era as it was inconvenient now, amid the euphoria of regained freedom and opening of borders between

the countries of the former Eastern bloc. This attempt to appropriate the monument’s symbolism found its

epilogue a year later when, following a heated public debate, the monument was removed and destroyed.

Projection organized by Deutscher akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD), in conjunction with

the exhibition Die Endlichkeit der Freiheit, took place on September 2 and 4, 1990

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Zion Square (Kikar Tziyon)

Jerusalem, 1990

In the projection, the artist alluded to the record-high levels of immigration of Jews from the Soviet Union

to Israel in the early 1990s, a phenomenon known as Exodus ’90. The site was a modern building housing

a bank and a hotel at the busy Zion Square. The projection inscribed itself in the structure of the tall building

with a glazed central part and sandstone-lined side breaks. On one of the latter the artist projected the image of

a hand holding a staff , a representation alluding to the Old-Testament Book of Exodus and the Wandering Jew

myth. On the other one, the image of a hand holding an exit visa and a suitcase, typical attributes of the Soviet

immigrants to Israel at the time.

Organized in conjunction with the exhibition Lifesize: A Sense of Real in Recent Art at The Israel

Museum in Jerusalem in the newly opened Nathan Cummings Building

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Tuxedo Royale, Tyne river, Newcastle Upon Tyne, 1990

“The Tuxedo Royale” was a ship (the former TSS-Dover passenger ferry), transformed in 1986 into a fl oating

nightclub moored on the River Tyne in Newcastle upon Tyne. The projection turned the Tuxedo Royale into

a symbol of the then policy of privatization and quick profi t derived from the conversion and sale of real estate

properties located in the city’s postindustrial quays and docksides, a process that caused the resettlement of

low-income inhabitants. The projection’s diff erent images were projected on the ship’s side from four projectors

installed on the wharf across the river.

Organized by First Tyne International, Newcastle upon Tyne in conjunction with the exhibition A New Necessity

production coordinator: Steve White

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Arco de la Victoria, 1991

The projection took place on Madrid’s triumphal arch commemorating General Franco’s nationalistic army’s

final victory over Republicans in the Spanish civil war. Situated in Plaza de la Moncloa, the arch has now also

been called Puerta de la Moncloa, refl ecting a desire to get it rid of its former meanings and erase the memory

of the times of Franco’s terror, at whose orders it was erected in 1956. Images of skeleton hands were projected

on two pillars of the single-span arch: one the one side, holding an M16 rifl e, on the other, clenching a fuel

nozzle. Under the statue of Minerva’s quadriga topping the arch, on the attic with a sculpted frieze and a Latin

inscription commemorating the 1937 victory, the question “Cuantos?” appeared (meaning both “how many” and

“how much”). In the projection, which took place in January 1991, three days after the start of the fi rst Gulf War,

which saw Spain join the US-led coalition, Wodiczko included the monument’s politics of non-memory in the

strategies of legitimizing current political interests.

Organized by Circulo de Bellas Artes in conjunction with the exhibition El Sueno Imperativo

[The Imperative Dream]